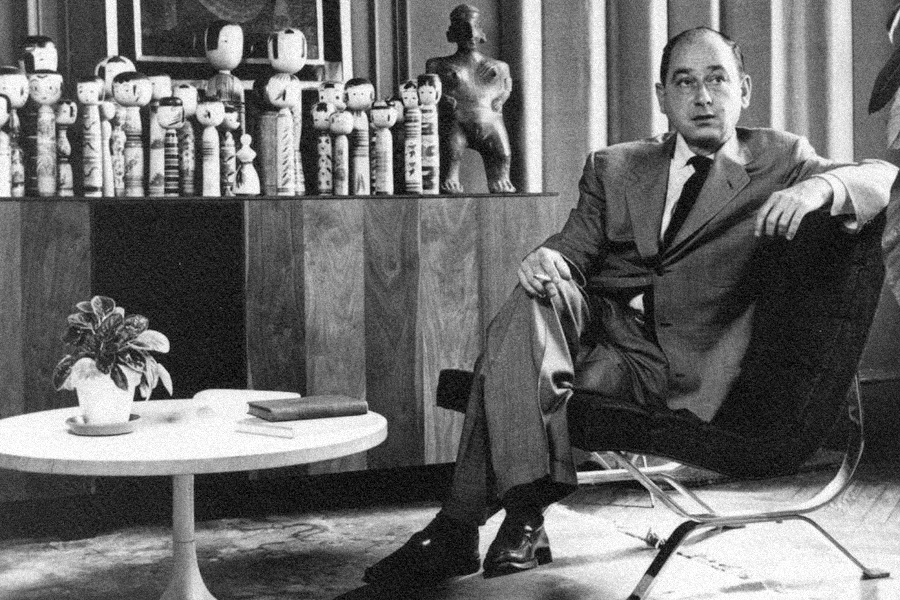

In fact, George Nelson had no intention of becoming an architect, let alone a designer. Like many people, he graduated from a public school and, having enrolled at Yale University, wanted to decide later on his specialty. But by chance, he saw the School of Architecture at the University as he was escaping a hurricane rainstorm.

Walking through the building, the future star of American design and architecture stumbled upon an exhibition of student work entitled ‘Cemetery Gate’. Half an hour later, the exhibition made George Nelson’s future – as an architect – clear.

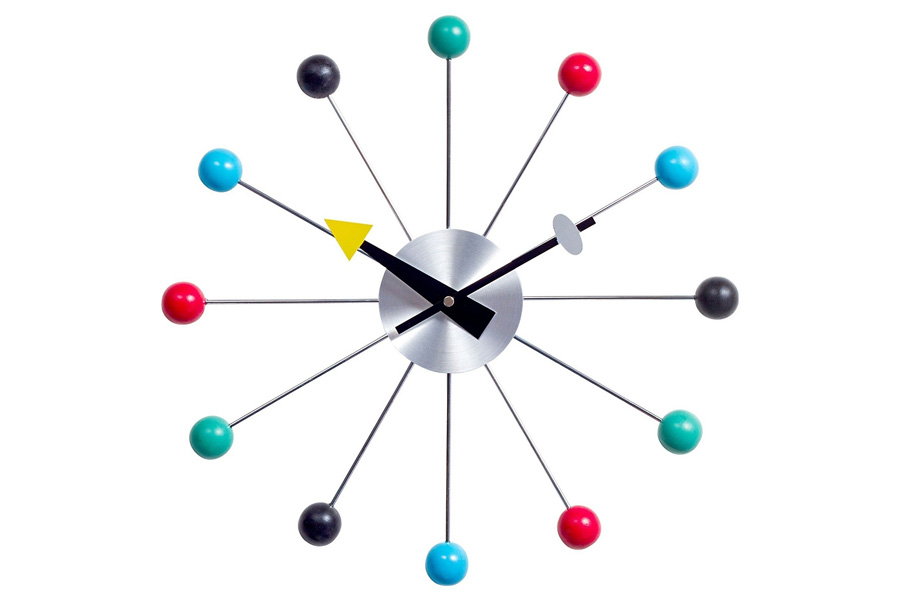

And it happened quite arbitrarily – from designing… wall clocks.

In 1946, Nelson founded the studio George Nelson Associates. A year later, Howard Miller commissioned him to create a collection of watches. First, Nelson analyzes how people use watches. In the end, two of George’s astute observations make this collection truly timeless:

In 1946, Nelson founded the studio George Nelson Associates. A year later, Howard Miller commissioned him to create a collection of watches. First, Nelson analyzes how people use watches. In the end, two of George’s astute observations make this collection truly timeless:

– First, people don’t need numbers to tell time; they look at the relative position of the hands to read it. Conclusion 1: The use of numbers is unnecessary.

– Second, most people wear a wristwatch to tell time, so the interior clock becomes a decorative element of the interior. Conclusion: clocks should be more decorative in nature.

It was these ideas that formed the basis of the first collection of 14 clocks, launched in 1949. It included wall clocks and compact table clocks, which were designed and produced in batches of 8 and had no names at first. It would seem …. but a fact! The Sunflower Clock, for example, was numbered 2261. It was a start, Ball clocks were the first. They were followed by Star, Sunburst, Spindle, Asterisks, Turnine, Eye and others, and over the next 35 years George Nelson Associates created over 130 models of clocks.

So who is he? George Nelson? Nelson is a man of many talents! Architect, designer, writer, central figure of mid-century American modernism.

Already as a student George came to recognition and popularity with the American public. This came about through articles and publications of his work in Pencil Points and Architecture magazines. Not yet graduating from Yale and studying architecture, Nelson was invited to join the architectural firm Adams and Prentice as a designer in his final year. He graduated from Yale with a degree in architecture in 1928 and became a teaching assistant in 1929, while earning a second bachelor’s degree at Yale. His enthusiasm for knowledge earns him a Master of Fine Arts degree, which he receives in 1931. The very next year, George is awarded the Rome Prize, a scholarship that allows him to study architecture with free accommodation in Rome from 1932 to 1934. But this city does not limit his interests and he travels extensively in Europe, discovering not only new architectural masterpieces but also becoming acquainted with the pioneers of avant-garde architecture.

The book Tomorrow’s House. New York, Simon and Schuster. 1945

In 1946, the future design legend founded his own studio, specializing in both architectural and industrial design, or design. And, of course, the first project of George Nelson’s studio was a shelving system called “Basic Storage Components.” This design, printed in a magazine, caught the interest of D. D. J. DePree, who at the time was looking for a new designer for the modern furniture factory owned by his brand, Herman Miller. In 1945, the company’s first catalog, prepared by the new designer, was produced, which met with great resonance among customers and competitors in the furniture industry. Thus began a famous collaboration – from 1947 to 1972 George Nelson was the permanent design director of Herman Miller. During this time, legendary figures such as Ray and Charles Eames, Harry Bertoy, Isamu Noguchi, Donald Norr and Richard Schultz – all of whom helped shape the bright name of Herman Miller – created and realized their designs with the brand under Nelson’s direction.

George Nelson & Associates CSS (Comprehensive Storage System). Herman Miller, USA, 1959. walnut, aluminium, enamelled steel, laminate, plastic, stainless steel.

Now working as a designer, George Nelson shaped the Action Office concept, and in the 1970s created an office system for the Nelson Workspace brand based on modular elements with the ability to simulate the space and the workspace itself. Nelson’s architectural office continued to work on new design challenges, including shaping corporate identity. Among the office’s clients were huge corporations: Abbot, Ford, Gulf, IBM, General Electric, Monsanto and Olivetti, and even the US government. Nelson attracted such well-known artists as Ettore Sottsass and Michael Graves to work on his projects. Together with them and independently, George Nelson created a new system of furniture and home furnishings.

George Nelson’s undisputed trademark as a designer was the Marshmallow sofa. He first introduced the design in 1956. Now experts call Marshmallow the prototype of pop art. The Marshmallow sofa was immensely popular among consumers of both private residences and office and gallery owners. To this day, it remains one of the most recognizable pieces of furniture in American design. The idea for this unusual sofa actually came about when an inventor of plastic discs came to Nelson’s studio and suggested using them to make an original piece of furniture. The discs themselves proved impractical, but the designers thought of replacing them with foam cushions upholstered in vinyl. Since then, George Nelson’s assistant, Irving Harper, is credited with co-creating the Marshmallow sofa. Eighteen colorful cushions, which visually resemble the colorful marshmallow candies popular in the US, were used to make the furniture. Each cushion is seen as a separate element of the sofa, while they are connected to each other by a fiberglass frame with steel legs. Thanks to the colorful range of colors, Marshmallow sofas can be combined to create seats of any length. And the cushions can be upholstered in any fabric or leather and can be easily removed for cleaning or replacement. Today, the Marshmallow sofa is produced on two continents: in America (by Herman Miller) and Europe (by Vitra). The 1959 Marshmallow sofa was sold at auction by Phillips de Pury & Company in December 2007 for $29,800.

Marshmallow Sofa. 1959

Nelson’s program invention is the Coconut chair, which has been in production since 1955. In its image, the model combines the accuracy of a minimalist style with the designer’s inherent strong sense of humor. In the image concept of the chair, George Nelson compares it to a coconut divided into eight parts. The seat is made of chrome-plated steel tubes, the seat is made of plastic and fiberglass, and the upholstery is made of fabric or leather. The Coconut armchair is ergonomically designed and intended primarily for relaxation. Nelson has managed not only to create a memorable and fashionable design, but to combine creative inspiration and engineering thinking in an innovative development.

In the 1930s Nelson works as a correspondent for architectural magazines, interviewing architects, modernists. During one such interview for Pencil Points magazine, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe asked Nelson about Frank Lloyd Wright, and George was deeply perplexed as he was unfamiliar with his work. A few years later Nelson would collaborate with Wright on a special issue of Architectural Forum magazine, which would be a kind of return from relative oblivion for Wright. It was with this magazine that he would be most closely and longest associated – he was the first associate editor from 1935 to 1943 and served as consulting editor from 1944 to 1949. This was his kind of professional and philosophical platform on which he defended and advocated modernist principles. His main idea was that a designer’s work should change the world for the better, and that a designer should not make unnecessary concessions to the commercial forces of industry. In his view, nature had already created everything beautiful, and man was destroying true harmony by not following nature, creating things outside its rules. Among his opponents and interlocutors in interviews and articles are such design giants as Eliot Noyes, Charles Eames and Walter B. Ford.

His architectural and design work goes hand in hand with his writing – after the war he co-authored Tomorrow’s House with Henry Wright. It is here that he introduces the concept of the ‘family room’ and the ‘storage wall’. With this, the idea of storage wardrobes was born and we regained the previously lost space between the walls. These two points become the starting points for George Nelson’s furniture designs. He came up with the idea for built-in wardrobes himself while writing a book, when his publisher asked George to complete and finish the chapter on home storage as soon as possible. At the time, both authors (Wright and J. Nelson) were not reinventing the wheel and asked themselves a simple question – “what’s in the wall?”. This is when the concept of between-the-wall storage was born. The book Tomorrow’s House was innovative for its time and proposed not only combining styles in one space as before, but also solving the problems that arise when furnishing and decorating any space. According to the book’s authors, the perennial lack of space in compact flats can be easily solved by turning a room wall into a double-sided (floor-to-ceiling) wardrobe or bookcase. The ingeniously simple idea has been welcomed by homeowners and furniture manufacturers alike. Manufacturing companies have thus achieved one of the most popular products by all categories of tenants.

Coconut Chair. 1955

The office theme was particularly revered by Nelson, and he designed more than one collection of office furniture in this line. The Nelson desk was introduced in 1958. The designer focused on the durability of both the design and the material – solid wood. The openings for access to all office gadgets – computer, phone – are an innovation in desk design. The calculated ergonomics of the table and the availability of a storage system for personal stationery have made it one of the most popular desks for employees.

The Wooden Concept workbench was originally designed exclusively for public facilities, but over time it has been increasingly used as home furnishings. Its modern design, combining thoughtful simplicity and spaciousness, its small size and unusual asymmetrical construction have appealed to connoisseurs of acutal design.

In 2008, Vitra reissued the Pretzel chair, one of its most famous designs, to celebrate Nelson’s 100th birthday. The anniversary edition was limited to just 1,000 pieces made of rosewood veneer. In 1952, Nelson designed a bentwood veneer chair and gave it a simple, almost technical name – the Veneered Chair. However, another name soon followed, an informal one – Pretzel, meaning ‘stool’. To achieve this austere effect, plywood was used in the manufacturing process to make the chair’s back and base, as well as four legs that curve elegantly under the seat. The tapered shape of the legs adds sophistication and refinement to the design of the chair.

Pretzel. 1952

Just one year after the presentation of the Pretzel chair, Nelson publishes his new book ‘Chairs’, in which he presents not only the history of seating furniture, but also analyses its current state, even predicting its future development. It is here that he first identifies the chair as one of the most important elements of modern furniture: “We can only speculate what furniture our future generation will consider to be the most typical of Western Europe in the first half of the 20th century, but I believe that the modern chair will certainly be on that list. In the book, he envisaged a completely new vision for this piece of furniture, its autonomy, without being linked to the composition of the walls in the interior. It was at this time that most designers began their first and most successful design experiments with chairs, transforming them into sculptural objects in the interior. “Lightness, transparency and elegant silhouette”, according to Nelson, were the most important qualities of a chair, and all these qualities are embodied in the Pretzel chair.

It should be noted that Nelson’s designs also covered other areas – he designed a typewriter for the Olivetti brand, the ‘Editor’. And in 1959, he essentially represented all of America by designing and organising the American National Exhibition in Moscow. He and his collaborators selected the United States’ finest industrial products and presented them on a wide three-dimensional platform that he designed specifically for the exhibition. At the exhibition, he also modelled the lives

The Ball Clock (1949) (Ball Clock) was one of the first 150 watches designed by George Nelson for the Howard Miller Clock Company, which sold the model from 1949 until the 1980s.

For us today, George Nelson is not only a representative of vibrant American design, but also the author of well-known classics: the atomic clock, the coconut chair, the animal clock, a host of emotional and memorable designs. Each of the objects created by Nelson carries positive thinking, incredible comfort and versatility, simplicity and clarity. Although today Nelson is considered a true classic of American design, his style is completely atypical of the American style and more in line with the tenets of the Italian movement. The time in which the master worked, and his talent, allowed him to combine the emotionality and humour of Italian design with American rationalism.

Text: © Ksenia Bandorina, PhD in art history, associate professor at the A.L. Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Industry

Source: St. Petersburg Designers’ Association

Pictures: Vitra.

One comment

Santori

January 29, 2024 at 6:41 pm

Джордж Нельсон – очень интересный архитектор. В канун Нового 2023 года в Париже, в Galerie Lafayette на Елисейских полях демонстрировалась целая выставка исторических предметов мебели, среди которых был и этот диван Marshmellow, а также большое количество других предметов. Мне настолько понравился этот диван, что захотелось узнать побольше об этом архитекторе. А тут как раз попалась на глаза эта статья.

Comments are closed.